Dale King studied the scriptures every morning of his life since his college days. He also loved reading the seventeenth-century English Puritans. A favorite, Richard Baxter said about death:

Dale King studied the scriptures every morning of his life since his college days. He also loved reading the seventeenth-century English Puritans. A favorite, Richard Baxter said about death:

“If a man that is desperately sick today, did believe he should arise sound the next morning; or a man today in desperate poverty, had he assurance that he should tomorrow arise a prince: would they be afraid to go to bed?”

He loved reading Spurgeon, the magnificent Victorian pastor, who admonished:

“Never fear dying, beloved. Dying is the last, but the least, matter that a Christian has to be anxious about. Fear living… that is a hard battle to fight, a stern discipline to endure, a rough voyage to undergo.”

“Never fear dying, beloved. Dying is the last, but the least, matter that a Christian has to be anxious about. Fear living… that is a hard battle to fight, a stern discipline to endure, a rough voyage to undergo.”

“A good character is the best tombstone. Those who loved you and helped you will be remembered when forget-me-nots have withered. Carve your name on hearts, not on marble.”

He loved the seventeenth- century British poets. His favorite, George Herbert, said:

“Only a sweet and virtuous soul,/ Like seasoned timber never gives./ But though the whole world turn to coal,/Then chiefly lives.”

John Donne, another seventeenth-century poet thundered:

“Death be not proud, though some have called thee/ Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so…./ Death shall be no more ; death, thou shalt die.”

So. Why all the quotations? My heart is so broken that I cannot do this. Words….Words….Words!So inappropriate a medium for measuring immeasurable grief and loss. Forgive me. I must borrow language. I must borrow from the Apostle John who, under the inspiration of the Spirit of God, resorted to outrageous understatement in rehearsing the untimely loss of a beloved and respected colleague:

So. Why all the quotations? My heart is so broken that I cannot do this. Words….Words….Words!So inappropriate a medium for measuring immeasurable grief and loss. Forgive me. I must borrow language. I must borrow from the Apostle John who, under the inspiration of the Spirit of God, resorted to outrageous understatement in rehearsing the untimely loss of a beloved and respected colleague:

“There was a man sent from God whose name was John [the Baptist]. He was not that light, but was sent to bear witness of that light.”

In my life, and in the life of thousands of other students spanning the globe for over six decades: “There was a man sent from God whose name was Dale….” He, too, in the sovereignty of God, from before the foundations of the world, was sent to bear witness of Christ, the Light.

One of the best days of my life was an early fall morning in 1975 when I sheepishly stepped into Dale King’s Victorian literature class. A man with sparkling, dancing eyes; a robust beard; a winsome smile; a zest for life and literature. And—for the first time in my life—I thought I must have encountered a saint with the gift of glossolalia! He spoke in another tongue—the tongue of angels?— and with the voice of God. I was at the burning bush: I spent my first hour as a liberal arts undergraduate desperately trying to write in a notebook—phonetically—each polysyllabic nugget that dropped from his lips.

He kept me after-class that day. I was terrified that he was going to tell me that liberal arts education was reserved for scholars, not back-woods, ignorant hicks such as I. Instead, he leaned back in his chair and thanked me—with grace, charm, and elàn—for transferring to Malone from a nondescript, non-accredited Bible institute, and for picking up on the biblical allusions from his selection of Victorian essays for that first day. While wooing me in that sonorous Dale-King tone, he tipped too far in his chair, fell backward into a deft backward roll that any accomplished gymnast would have had to respect, picked himself up, returned to his chair, and, all the while, kept right on talking—didn’t miss a beat.

He kept me after-class that day. I was terrified that he was going to tell me that liberal arts education was reserved for scholars, not back-woods, ignorant hicks such as I. Instead, he leaned back in his chair and thanked me—with grace, charm, and elàn—for transferring to Malone from a nondescript, non-accredited Bible institute, and for picking up on the biblical allusions from his selection of Victorian essays for that first day. While wooing me in that sonorous Dale-King tone, he tipped too far in his chair, fell backward into a deft backward roll that any accomplished gymnast would have had to respect, picked himself up, returned to his chair, and, all the while, kept right on talking—didn’t miss a beat.

I fell in love. Hopelessly. Irrevocably. Soul-mates. Forever. My years at Malone, both as a student and, later, as a professor, were rich times, indeed: a few moments to rub shoulders with remarkable mentors in the Kingdom of Christ: Bob and Zovinar Lair, Burley Smith, John Bricker, Coach Bob Starcher, Carlene King. Never, however, had I met another man like Dale.

The poet, J. Frederick Nims, in “Love Poem” attempts to capture the essence of such a beloved one. Nims admits that his wife is “his clumsiest dear,” one who is “a wrench in clocks and the solar system;” that is to say, she is someone who is clearly not a candidate to host a home-repair show.

Neither was Dale. He was not the one to set the timing on your carburetor or to trim back the giant oak tree towering over your house. In the words of Nims, he had “no cunning” in fix-it situations, EXCEPT:

Neither was Dale. He was not the one to set the timing on your carburetor or to trim back the giant oak tree towering over your house. In the words of Nims, he had “no cunning” in fix-it situations, EXCEPT:

“Except all ill-at-ease figiting people.

The refugee uncertain at the door,/You make at home.

Deftly you steady the [broken, the reeling] on his undulant floor….

….Only/with words and people and love you move at ease

In traffic of wit expertly Maneuver/and keep us/all devotion at your knees….”

When I met Dale, I was hopeless. Raised in the shadows of the soot- belching smokestacks of Plant two of the Firestone factory in Akron, imagination was the only resource I had. It was the only escape one had from a world that seemed to have little opportunity, when all one ever saw was what was outside the front door. By high-school graduation, hope had been beaten out of me. I was broke, and I was broken. Ill-at-ease. Suicidal. God used Dale and Carlene to save my life, and to give me one. Dale tried his best to teach me literature but—far more than that—he gave me hope. (The apostle Paul insists in the conclusion of his letter to the Romans that we are saved by hope.) In the wonderful film Saving Mr. Banks, Walt Disney echoes the primacy of hope in a remonstrance to Pamela Travers, the author of Mary Poppins:

When I met Dale, I was hopeless. Raised in the shadows of the soot- belching smokestacks of Plant two of the Firestone factory in Akron, imagination was the only resource I had. It was the only escape one had from a world that seemed to have little opportunity, when all one ever saw was what was outside the front door. By high-school graduation, hope had been beaten out of me. I was broke, and I was broken. Ill-at-ease. Suicidal. God used Dale and Carlene to save my life, and to give me one. Dale tried his best to teach me literature but—far more than that—he gave me hope. (The apostle Paul insists in the conclusion of his letter to the Romans that we are saved by hope.) In the wonderful film Saving Mr. Banks, Walt Disney echoes the primacy of hope in a remonstrance to Pamela Travers, the author of Mary Poppins:

“That’s what we story-tellers do. We restore order with imagination. We instill hope again, and again, and again.”

What Dale did for me is redolent of a scene in Wendell Berry’s magnificent tale “Nearly to Fair,” in his book That Distant Land. In this story, a kind, gentle man comes across a small boy who has just been verbally abused (a staple in this child’s life) and left sobbing and cowering on the sidewalk. Dale, like the man in the story, looked at me in all my cowering, shivering, craven fear—looked into my bankrupt heart and announced to the whole world: “If you don’t mind, I’m going to borrow this boy for a while.” He picked me up, nestled me into his capacious heart—and he loved me.

What Dale did for me is redolent of a scene in Wendell Berry’s magnificent tale “Nearly to Fair,” in his book That Distant Land. In this story, a kind, gentle man comes across a small boy who has just been verbally abused (a staple in this child’s life) and left sobbing and cowering on the sidewalk. Dale, like the man in the story, looked at me in all my cowering, shivering, craven fear—looked into my bankrupt heart and announced to the whole world: “If you don’t mind, I’m going to borrow this boy for a while.” He picked me up, nestled me into his capacious heart—and he loved me.

More than my teacher, more than my dear friend, more than my most-loved colleague – he was my dad. To Dale, and the love of Christ that emanated from him, I owe everything. I would not have survived without him. Scores of his students surely must echo that same sentiment.

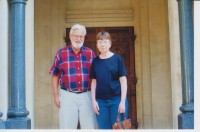

His crowning achievement, however, is that of winning the heart of his dear wife Carlene: She was my best teacher. Smartest person I know. The very definition of savoir-faire. An avatar of grace and charm.Her extension of friendship and love, one of the best things that ever happened to my wife.The final arbiter in all matters sartorial or gustatorial. I am ashamed in expressing my grief in front of her; I am faced with my selfishness. Forgive me, Carlene. Your grief must seem inconsolable.

Yet a little while, Carlene, and all of us who have tasted of the grace of Christ will re-unite with Dale in a place unencumbered by time or grief or doctor appointments, or medication. And Dale will have the Jordan Pond bars. And the party will begin.

Yet a little while, Carlene, and all of us who have tasted of the grace of Christ will re-unite with Dale in a place unencumbered by time or grief or doctor appointments, or medication. And Dale will have the Jordan Pond bars. And the party will begin.