Meredith wrote this last Friday, the day Bocca died. We wrote our own memorials so we would have more memories of our wonderful kitty.

Loving Bocca

“We’re not going to be able to bring him home until next week,” Matt explained. To my confused look, he replied, “Well, you see, he’s … different. He was in the shelter’s Socialization Program – it’s for, well, I guess what you’d call Special Needs kitties. If people want to adopt one of these cats, they have to wait a week – the shelter wants to make especially sure they’re committed to the adoption.”

“I see. And what kind of ‘Special Need’ does he have?”

“Uh, well, they think he might not adjust well to the new environment at first. But he was so cute and sweet in the shelter, I just had to pick him. He picked me, really.”

Returning from the shelter a week later, Matt brought the box into our bedroom and opened it. I got only a blurry glimpse of tiger stripes as the cat scrambled frantically out of the box and under our queen-sized bed, stopping at its exact center, just out of reach and impervious to our entreaties that he come closer. All I could see were its glowing green eyes.

When we realized that the cat had no intention of coming out from under the bed anytime soon, we shoved bowls of food and water under there with him – shortly followed by a litter box. “Cats can live a long time,” I reminded Matt. “Are we going to be shoving food, water, and litter under the bed for the next eighteen years or so? I mean, we’ll do what we have to, but it’s not exactly what I had in mind for cat ownership.”

As it turned out, we only had to do this for about three weeks, and even toward the end of that time, the cat would come closer to our outstretched hands. The first day he let me touch him, I felt we’d had a breakthrough only slightly less miraculous than that of Anne Sullivan with Helen Keller. Several days later, he finally came out from under the bed for short spells. And several days after that, he was roaming throughout the apartment.

Though we’d chosen the name “Bocca” – Italian for “mouth” – before bringing him home, the name proved an apt one: he loved to talk, and he loved to eat. His voice was not the most dulcet-toned of meows, but he generally saved his particularly strident vocalizing for when he wanted food. We said he was world’s sweetest kitty everywhere except in the kitchen. To distract him while we dished up his food, we would sing him one of the little songs we made up: “What is it, Bocca? (3x) Oh, why do you cry so? Why do you cry? (3x) Oh, why do you cry so?” This one we sang in harmony. The other one didn’t lend itself so easily to a harmony part, but had an echo: “Bocca Bo-Sweet (Bocca Sweet, Bocca Sweet), on his little kitty feet (kitty feet, kitty feet) – oh, we sure think he’s neat (think he’s neat, think he’s neat) – he’s Bocca Bo-Sweet (Bocca Sweet, Bocca Sweet).”

Not surprisingly, given his appetite, Bocca got rather large – about twenty pounds, at his heaviest. When one of our friends came over for dinner and saw him for the first time, she gasped and said, “That cat looks as if he’s swallowed a meatloaf!”

The only thing Bocca craved more than food was love. We used this to explain his size, telling ourselves, “It takes a lot of cat to hold that much love.” Some people think of cats as aloof, but this one certainly wasn’t. He got into the habit of waiting by the door when he knew I was about to come home. Then, when I tried to walk in, he’d flop down in front of my feet until I gave him some loving attention.

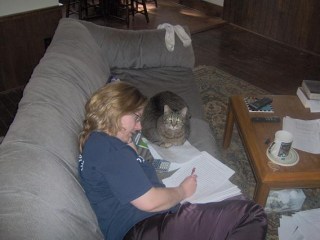

For a long time, Matt was his favorite if we were on the couch. Matt preferred to eat Roman-style, reclining, and Bocca would curl up next to his stomach. He had an aversion to laps – unless we covered our laps with blankets. During the last couple years, the blankets were no longer necessary, and our sitting down was often enticement enough for him to come running to make himself comfortable, giving us a firm head-butt if we forgot to keep petting him.

At night, Bocca was more likely to sleep on my side of the bed, usually down by my feet, but if he sensed me waking up, he’d move to be by my head or chest, where I could reach him to rub his belly or scritch his ears. Because of his ongoing eagerness for affection, we called him the Love Sponge – he soaked it all up.

Whenever we went away on trips, Bocca would mark our return by not letting us out of sight for at least an hour or so, following us from room to room as if to make sure we weren’t about to leave again.

Bocca’s gentle, loving nature also kept him from being aggressive with our two other cats – which is fortunate, since for most of his life the “Meatloaf Kitty” was almost as big as the two of them put together, and could probably have done some real harm if he’d been so inclined. But they picked on him decidedly more often than he picked on them, and we’d urge him to overcome that sweet, pacifist nature and put the littler ones in their place. When he wouldn’t, we’d intervene, chasing the others to different rooms for “kitty time outs” while we comforted Bokey.

While he almost never started fights with our other cats, Bocca had no qualms about releasing any pent-up hostilities on rodentkind. His first Christmas with us, one of our relatives had given us a stuffed cat-toy – a mouse about the size of a large rat. We tossed it to Bocca to see what he’d do with it. He immediately grabbed its head in his mouth, rolled over on his back, and, in just seconds, disemboweled it with the claws of his hind feet. Stuffing was everywhere, so the first time he got to play with this toy was also the last.

At the time, we wondered if Bocca would prove similarly fierce if he encountered a real mouse. Several mice later, we now know the answer – although he never disemboweled any (thank goodness), he was indeed a capable mouser, and proud of his skills. In fact, my first day of summer vacation, when I’d been so looking forward to sleeping in, began much too early, as I was awakened by his muffled cries of triumph – muffled because he had a mouth full of mouse, of course.

That was only six or seven weeks ago. That particular “Bocc-alarm” was not the reveille with which I’d wished to begin my long-awaited break, but I’d give much to hear it again. We’d noticed Bocca getting thinner – too rapidly, we feared, and yet besides increasing boniness he had no other symptoms of ill health. If anything, he seemed healthier in some ways – when heavier, he had sometimes wheezed while he slept, or had had trouble jumping up onto the bed. At this lighter weight, he was able to leap nimbly from the back of one couch to another, something we’d never seen him attempt in his younger but fatter days.

Because of the weight loss, we had taken Bocca to the vet in January, but no problems were found. In the ensuing months, he gained back a couple pounds, and we assumed he’d be with us for a few more years. But then the weight loss happened again, more quickly and more drastically than before. When his voice started to become higher and feebler, and when he began spending time in half-hidden nooks and crannies he’d never frequented previously – like beside the toilet, or at the back of the linen closet – we made another appointment with the vet.

It was too late – some disease we never caught the name of, but the prognosis was clear: several months at the most, if he responded to the medications.

Bocca used to be such a strong cat that we were physically incapable of forcing him into his carrier, so whenever it was time to update his vaccinations, we’d find a vet who made housecalls. I still remember coming home from work one day and being met at the door by Matt. Agitated and breathing hard, he opened the door only a crack to say, “The vet and I are having trouble cornering Bokey. It isn’t pretty. Why don’t you take a walk around the block a few times before coming back?” From inside, I heard the frantic yowls of a terrified cat, and decided I’d take my husband’s advice about that walk.

Moving from Chicago was wretched. Bocca’s panicked yowlering, from a carrier on the front seat of the U-Haul, was shredding Matt’s nerves so badly before we even left the city that he recruited the aid of his mother and her boyfriend – one of them drove their car and one drove mine, so that I could sit in the cab of the truck with Bocca, petting him constantly, all the way to Ohio, to keep him quiet.

It wasn’t like that this time. Too weak to put up much physical or verbal protest, Bocca let Matt take him to the vet for the diagnosis and pills. And then back again a couple days later, for longer-lasting shots, because we couldn’t get him to swallow the pills. And then back again for fluids, because we couldn’t get him to eat or drink.

The vet visits of the past couple weeks were a far cry from those early housecalls, but in one way Bokey had come full circle: he was once again back in our bedroom. He’d started his years with us in the bedroom solely because the bed was the most immediate sanctuary he found when Matt first opened his box. This time, though, he was with us by choice – ours and his. We wanted to be close to this creature who’d given us so much joy and asked only for food and affection in return. Not content to be on the floor, where he had access to food, water, and litter, but lacking the strength to jump up on the bed to join us, he would cry or look up at us piteously until we put him on the bed between us, where he could be loved and petted from both directions.

Even this morning, he wanted to be with us. Even this morning, when it had been several days since he’d eaten or drunk on his own. Even this morning, when he could no longer hold his head up, and his breathing became labored. Matt called the vet one more time.

The earliest appointment we could get was at 11:00. I had to do some work in my classroom, so Matt and I walked to school together, and back again a little after 10:30. He brought up the cat carrier from the basement. Unable to say so, we both knew the carrier would be coming home empty.

Matt didn’t bother to bring the carrier into the vet’s with us – he just lifted Bocca gently into his arms and held him on his lap in the waiting room, while I petted him. As Bocca struggled to breathe, Matt and I did too, choking on our tears. One of the vet’s assistants brought us a box of tissues, and the other woman waiting, who’d been there before us, urged the vet to see us first. We brought Bocca into the room and laid him on the table. The vet got out his stethoscope and listened for a heartbeat, but found none. Bocca had passed away in Matt’s arms only moments before, giving us the last gift it was in his power to bestow: he spared us from deciding that we had to have him put to sleep.

On that harrowing moving-day ride through Chicago, eight years ago, my own stress and hormones were taking their toll, despite the fact that I was driving my own car at that point, and wasn’t even within earshot of Bokey’s heartrending howls. Praying aloud that Bocca would calm down, would not be so scared, would stop crying, I began crying myself. “God, please,” I wailed. “He’s just a kitty – he never gave us anything but love!” I cried the same prayer again today.

I know he was “only a cat.” I know there are people going through far worse ordeals, and I know lots of people have gone through this one. I know. I do. But I miss him so much. That Special Needs kitty Matt brought home just a couple months after we got married has been one of my life’s most consistent blessings over the past eleven years. And although I’m not sure what the situation will be regarding animals in heaven, I’m really hoping that when I one day reach my own “mansion just over the hilltop,” I’ll open the door to find a green-eyed tiger cat flopping down in front of my feet, meowing insistently as if to say, “Thank goodness you’re finally home!”